"........hier

sind ein paar Artikel über Vedische Organische Landwirtschaft, - die

meisten davon eigentlich mehr organische naturnahe (so will ich sie mal

nennen) Landwirtschaft und zwei speziell über Maharishi Vedic

Agriculture, welche sehr schön (einer in englischer Sprache, der text

file in Deutsch) das Prinzip erklären, was das Spezielle daran ist.

"........hier

sind ein paar Artikel über Vedische Organische Landwirtschaft, - die

meisten davon eigentlich mehr organische naturnahe (so will ich sie mal

nennen) Landwirtschaft und zwei speziell über Maharishi Vedic

Agriculture, welche sehr schön (einer in englischer Sprache, der text

file in Deutsch) das Prinzip erklären, was das Spezielle daran ist.Andere Maßnahmen bzw. Praktiken, die in der biolandwirtschaftlichen Weise ausgeübt werden, sind hier nicht im Einzelnen erwähnt, sind aber doch impliziert. Interessant auch der Artikel, der zeigt, dass die organische Anbauweise durchaus konkurrenzfähig ist und oftmals - speziell in den Tropen - sogar überlegen. Es bedarf also weiß Gott nicht all dieses kompliziert genetisch veränderten Zeugs zur Lösung der Welthungerkrise - wobei es mir manchmal so vorkommt, als ob diese erst durch die "modernen" Vorgehensweisen erst erzeugt wurde - zumindest teilweise.

Die Indios am Amazonas haben gezeigt, wie man mit natürlichen Mitteln selbst in den Tropen, wo sich die Böden bei falscher Arbeitsweise sehr schnell in Wüsten verwandeln können, nachhaltig fruchtbare landwirtschaftliche Böden schaffen kann,- sie scheinen, so wie sich mir diese beiden Berichte darstellen, vedische Prozeduren angewendet zu haben (beide Artikel in Deutsch). Auch Fukuoka hat verfeinerte naturnahe Vorgehensweisen gefunden, um selbst stark erodierte Böden wieder kulturfähig zu machen. Über Masanobu Fukuoka findet man sicher auch das eine oder andere im Internet in deutscher Sprache, da ja seine Bücher auch ins Deutsche übersetzt wurden.

Die Titel dieser Bücher lassen schon das anklingen, worüber wir am Nachmittag gesprochen hatten: "Rückkehr zur Natur. Die Philosophie des natürlichen Anbaus", "In Harmonie mit der Natur. Die Praxis des natürlichen Anbaus", "Die Suche nach dem verlorenen Paradies. Natürliche Landwirtschaft als Ausweg aus der Krise" und "Der große Weg hat kein Tor". Es lohnt sich, alles mal in aller Ruhe nach und nach zu studieren, um sich ein Bild zu verschaffen. Beginne erst mal mit "Organic Agriculture can feed the World", dann "Gesunde Nahrung ...." und "Maharishi Vedic Agriculture", usw. Viel Spaß!........

GESUNDE NAHRUNG FÜR EIN GLÜCKLICHES LEBEN Vedisch, ökologische Landwirtschaft Auszug aus Maharishis neuem Buch "Ideal India", Maharishi Channel, 23.5.01 / Übersetzung: Jörg Schenk

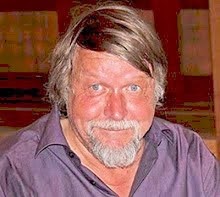

Das nachstehende Foto zeigt den genannten indischen Weisen recht kurz vor seinem Tod im Alter von ca. 95 Jahren:

MAHARISHI:

"Wir fügen zu dem Wort "ökologisch" das Wort "Vedisch" hinzu, weil

"Vedisch" Wissen bedeutet, vollständiges Wissen. Wenn man also das Wort

"Vedisch" hinzufügt, dann beschreibt man damit, dass man die

Organisationskraft des Gesamtwissens im Bereich der Landwirtschaft

anwendet. "Vedisch ökologisch" bedeutet, eine ökologische

Landwirtschaft, die durch den nährenden Einfluss von Ved bereichert wird

- der nährende Einfluss des Naturgesetzes, wie er in den Melodien der

Vedischen Klänge, die Melodien der Vedischen Literatur, vorhanden ist.

Das Naturgesetz ist die Intelligenz der Natur, die alle Gesetze der

Natur, die für die Schöpfung, die Evolution und für die Zyklen des

Lebens verantwortlich sind, formiert. Die

kreativen Impulse der Naturgesetze, die Vedischen Vibrationen, sind die

Vibrationen, die den nährenden Einfluss der evolutionären Qualität der

Naturgesetze in sich tragen. Dieser Einfluss ist für das Wachstum und

den Nährwert der Pflanze ganz wesentlich.

MAHARISHI:

"Wir fügen zu dem Wort "ökologisch" das Wort "Vedisch" hinzu, weil

"Vedisch" Wissen bedeutet, vollständiges Wissen. Wenn man also das Wort

"Vedisch" hinzufügt, dann beschreibt man damit, dass man die

Organisationskraft des Gesamtwissens im Bereich der Landwirtschaft

anwendet. "Vedisch ökologisch" bedeutet, eine ökologische

Landwirtschaft, die durch den nährenden Einfluss von Ved bereichert wird

- der nährende Einfluss des Naturgesetzes, wie er in den Melodien der

Vedischen Klänge, die Melodien der Vedischen Literatur, vorhanden ist.

Das Naturgesetz ist die Intelligenz der Natur, die alle Gesetze der

Natur, die für die Schöpfung, die Evolution und für die Zyklen des

Lebens verantwortlich sind, formiert. Die

kreativen Impulse der Naturgesetze, die Vedischen Vibrationen, sind die

Vibrationen, die den nährenden Einfluss der evolutionären Qualität der

Naturgesetze in sich tragen. Dieser Einfluss ist für das Wachstum und

den Nährwert der Pflanze ganz wesentlich.Es gibt 40 elementare Klangstrukturen - 40 Qualitäten des Vedischen Klanges, die alle verschiedenen Struktur- und Funktionsaspekte der Pflanze formieren: die Physiologie der Pflanze und die Intelligenz, die die Pflanze erschafft und sich durch sie ausdrückt. Diese 40 Qualitäten der Intelligenz sind die Gesetze der Natur. Sie sind in ihrer konzentrierten Form im Samen einer Pflanze lebendig. Wenn der Same sprießt und heranwächst fördern die 40 Qualitäten der kreativen Intelligenz zusammen die Entwicklung jeder einzelnen Faser der Pflanze, damit diese all ihre materiellen Aspekte voll entfalten kann.Die 40 Qualitäten bilden die vollständige Intelligenz: die Information, die in jeder feinsten Faser der Pflanze enthalten ist, während sich der materielle Aspekt von der abstrakten, unmanifesten Ebene der Intelligenz des Saftes aus, ausdrückt - die Entwicklung vom unmanifesten Wert zum manifesten Wert.

Wenn diese Melodien auf dem Feld gesungen werden, dann werden die 40 Werte der reinen Intelligenz, Ved, vollständig belebt und gelangen zu ihrer vollen "Blüte". Der heilende und nährende Einfluss der Vedischen Klänge wurde nicht nur im Leben des Menschen sondern auch im Reich der Tiere und der Pflanzen bereits ausführlich durch wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen dokumentiert.Wenn die natürlichen Klänge der Natur, die Klänge des Naturgesetzes, die Klänge des Ved, gesungen werden, dann resonieren sie mit dem strukturierten Klang in der Natur und beleben und aktivieren das Leben von seiner Basis aus und beeinflussen so jede Ebene der Evolution - vom Individuum bis zum Kosmos.

Die Vedischen Melodien, die Vedischen Rezitationen, sind so aufgebaut, dass es für jede Stufe im Wachstum einer Pflanze eine geeignete Melodie gibt, um die volle Entfaltung dieser Entwicklungstufe zu erreichen. Die Pflanze kann so auf jeder Stufe ihrer Entwicklung ihre vollständige Struktur und Funktion entfalten - für ihren vollen Nährwert und ihre lebensunterstützenden Werte. Wenn die Vedische Qualität zur ökologischen Landwirtschaft hinzugefügt wird, dann ist das eine Sache von Intelligenz, eine Sache von Bewußtsein, ein Vorgang, bei dem die kreative Intelligenz der Natur direkt genutzt wird, um die verschiedenen Evolutionstufen der Pflanze und ihren Nährstoffen zu unterstützen.

Wenn der Unterschied zwischen der konventionellen und der ökologischen Landwirtschaft erkannt worden ist, dann wird als nächster Schritt das Vedische Element hinzugefügt, um so einen nährenden Wert zu schaffen. Der Vedische Wert wird hinzugefügt, damit unsere Nahrung vollkommen nährend und kraftvoll wird. "Maharishis vedische ökologische Landwirtschaft" bietet deshalb die bei weitem nahrhafteste Nahrung. Das Element "Vedisch" ist für den Bereich der "ökologischen Nahrung" ein "Geschenk". "

Maharishi Vedisch-Biologische Landwirtschaft

Reichliche Mengen gesundheitsfördernder Nahrungsmittel durch vedisch-ökologische Landwirtschaft

Angesichts der schädlichen Auswirkungen konventioneller Agrartechnologie auf Gesundheit und Umwelt ist eine globale Erneuerung der Landwirtschaft dringend notwendig. Es ist das Ziel der Maharishi Vedisch-Biologischen Landwirtschaft, die heutige Krise der Landwirtschaft durch eine wirklich Globale Grüne Revolution zu überwinden - eine Grüne Revolution, die den Landwirten und ihren Familien Wohlstand und Höheres Bewusstsein bringt, der gesamten Weltbevölkerung reichlich gesundheitsfördernde Nahrung und das Gleichgewicht in der Natur aufrecht erhält.

Die

heute angewandten konventionellen Agrarmethoden belasten mit

schädlichen chemischen Düngemitteln, nicht abbaubaren Pestiziden und

Herbiziden sowie gentechnisch veränderten Pflanzen die Umwelt inzwischen

in größtem Ausmaß und sind eine ernsthafte Bedrohung für die

menschliche Gesundheit geworden. Gleichzeitig hält das praktizierte

System die Bauern arm und schadet deren Gesundheit. Es ist

verantwortlich für Bodenerosion, Verschmutzung von Wasser und Luft,

vergiftete Erzeugnisse, Beeinträchtigung des Klimas bis hin zu

Naturkatastrophen und den damit verbundenen Missernten und

Einkommenseinbußen der Landwirte. Dabei wird das erklärte Ziel, die

Weltbevölkerung ausreichend zu ernähren, keinesfalls erreicht.

Der

konventionelle Anbau, der hauptsächlich eine große Quantität der Ernten

zum Ziel hat, berücksichtigt in seinen Methoden nur spezifische,

isolierte Naturgesetze, lässt jedoch die meisten anderen und die

Gesamtheit des Naturgesetzes außer acht. Dementsprechend liegen seine

Erfolge nur in Teilbereichen wie, z.B. Menge, Haltbarkeit,

gleichförmiges Aussehen. Der Nährwert der Erzeugnisse, die Umwelt und

die Gesundheit des Bauern und des Konsumenten leiden jedoch.

Nur

ein Landwirtschaftssystem, das alle Naturgesetze berücksichtigt, das im

Einklang mit der Gesamtheit des Naturgesetzes steht, kann Erzeugern,

Konsumenten und Umwelt gleichermaßen gerecht werden und Produkte

höchster Qualität erzeugen. Maharishi Vedisch-Biologische Landwirtschaft

nutzt zusätzlich zu den bekannten Methoden der biologischen

Landwirtschaft Verfahren und Technologien, die alle Aspekte des

Naturgesetzes miteinbeziehen: Vedische Bewusstseinstechnologien zur

Entwicklung höherer Bewusstseinszustände der Bauern sowie Vedische

Rezitationen zur Förderung der Vitalität und inneren Intelligenz der

Pflanzen. Weiterhin bedient sie sich der Vedischen Astrologie - Jyotish -

zur Ermittlung des optimalen Zeitpunktes für jede Phase des Anbaus

sowie der Prinzipien der Vedischen Architektur, die die Einheit des

Menschen mit dem Kosmos fördert.

Nur

ein Landwirtschaftssystem, das alle Naturgesetze berücksichtigt, das im

Einklang mit der Gesamtheit des Naturgesetzes steht, kann Erzeugern,

Konsumenten und Umwelt gleichermaßen gerecht werden und Produkte

höchster Qualität erzeugen. Maharishi Vedisch-Biologische Landwirtschaft

nutzt zusätzlich zu den bekannten Methoden der biologischen

Landwirtschaft Verfahren und Technologien, die alle Aspekte des

Naturgesetzes miteinbeziehen: Vedische Bewusstseinstechnologien zur

Entwicklung höherer Bewusstseinszustände der Bauern sowie Vedische

Rezitationen zur Förderung der Vitalität und inneren Intelligenz der

Pflanzen. Weiterhin bedient sie sich der Vedischen Astrologie - Jyotish -

zur Ermittlung des optimalen Zeitpunktes für jede Phase des Anbaus

sowie der Prinzipien der Vedischen Architektur, die die Einheit des

Menschen mit dem Kosmos fördert.

Das

Ergebnis sind vitale, widerstandsfähige Pflanzen, Ernten mit einem

hohen Gehalt wertvoller Nährstoffe, eine gesunde Umgebung für den

Landwirt, Bewahrung der natürlichen Bodenqualität und des ökologischen

und klimatischen Gleichgewichts. Die Bauern erzielen aufgrund hoher

Fruchtbarkeit des Saatguts und der Böden sowie idealer Wetterbedingungen

zuverlässig große Erträge an hochwertigen Nahrungsmitteln und damit ein

hohes Einkommen. Die Bevölkerung wird reichlich mit

gesundheitsfördernden Nahrungsmitteln versorgt, die das Gleichgewicht

von Körper und Geist fördern, Denken und Handeln der Menschen in eine

zunehmend evolutionäre Richtung bringen und durch ihren Intelligenzwert

die Entwicklung höherer Bewusstseinszustände unterstützen.

Ein

sehr wichtiger Aspekt zur Erzeugung hochwertiger Nahrung ist der

Zeitpunkt der Ernte. Untersuchungen haben gezeigt, dass der vollständige

Nährwert in der Periode kurz vor der vollständigen Ausreifung der

Frucht entwickelt wird. Früchte, die vor Beendigung des Reifevorgangs

geerntet werden, wie es heute zur Erzeugung billiger Massenprodukte

üblich ist, können ihren optimalen Nährwert nicht entfalten. Selbst

biologisch angebaute Früchte, die unreif geerntet werden, erzielen keine

optimale Qualität. Maharishi Vedisch-Biologische Landwirtschaft lässt

die Früchte vollständig auf der Pflanze reifen, so dass diese eine

optimale gesundheitsförderliche - man könnte sagen nektargleiche -

Wirkung auf den Konsumenten haben.

Maharishi

Vedisch-Biologische Landwirtschaft ist der wichtigste Aspekt bei der

wirtschaftlichen Hilfe für Entwicklungsländer. Maharishis Programm zur

Beseitigung der Armut sieht den Aufbau landwirtschaftlicher Kooperativen

in den 40 ärmsten Ländern der Welt vor. Der Anbau hochwertiger Produkte

auf neu kultivierten, gesunden, giftfreien Agrarflächen und deren

weltweiter Export sichert den Bauern ein gutes Einkommen und finanziert

darüber hinaus eine ideale Infrastruktur und eine Gruppe Kohärenz

schaffender Experten in Maharishis Vedischen Bewusstseinstechnologien,

die dauerhaften Frieden und Wohlstand für die Region sichert.

Pressemitteilungen

5. Dezember 2005Maharishi will mit 10 Billionen Dollar die Armut aus der Welt schaffen

4. August 2004: Neue Untersuchung zeigt: Maharishi Honig verfügt über besondere Vitaleigenschaften

14. November 2002: "Vedische Landwirtschaft erzeugt Nektar und kein Gift"

4. August 2004: Neue Untersuchung zeigt: Maharishi Honig verfügt über besondere Vitaleigenschaften

14. November 2002: "Vedische Landwirtschaft erzeugt Nektar und kein Gift"

Forschung

Lesen Sie bitte auf Englisch: http://maharishi-programmes.globalgoodnews.com/vedic-agriculture/research.html

http://www.globalesland.de/programme/landwirtschaft.phphttp://www.maharishi.de/index.php?MEDITATION=./VEDA/PROGRAMME/LANDWIRTSCHAFT/

http://www.maharishi.de/index.php?MEDITATION=./VEDA/PROGRAMME/LANDWIRTSCHAFT/NAHRUNG/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fukuoka Masanobu

Fukuoka Masanobu (jap. 福岡正信; * 2. Februar 1914) war zunächst Mikrobiologe und wurde dann Bauer. Seine Bücher sind Standardwerke in der Permakultur.

Das Konzept des japanischen Bauern für die natürliche Landwirtschaft lautet: Die Natur ist in der Lage, sich selbst zu erhalten, sie bedarf menschlicher Eingriffe nicht. Masanobu Fukuoka wurde auch durch seine doppelte Fruchtfolge ohne Pflügen am selben Standort bekannt.

Zur Bodenbedeckung und -verbesserung insistiert Fukuoka besonders auf dem Weißklee.

Werke

- Der große Weg hat kein Tor, Pala-Verlag, 1984, ISBN 3- 923176-14-7

- Masanobu Fukuoka: Rückkehr zur Natur. Die Philosophie des natürlichen Anbaus, Pala-Verlag, September 1998, ISBN 3-923176-46-5

- Masanobu Fukuoka: In Harmonie mit der Natur. Die Praxis des natürlichen Anbaus, Pala-Verlag, Oktober 1998, ISBN 3-923176-47-3

- Masanobu Fukuoka: Die Suche nach dem verlorenen Paradies. Natürliche Landwirtschaft als Ausweg aus der Krise, Pala-Verlag , Januar 1999, ISBN 3- 923176-63-5

Weblinks

(englischsprachig)

Natürliche Landwirtschaft (http://www.fukuokafarming.net/) und

The Fukuoka Farming Website (www.larryhaftl.com/ffo/)

Seed Balls.com (http://www.seedballs.com/)

July 1982 Plowboy Interview (http://www.motherearthnews.com/library/1982_July_August/The_Plowboy_Interview__Masanobu_Fukuoka)

(Zusammenfassung der „Strohhalm-Revolution“)

=======================================================================

Quotes

"The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings," - Masanobu Fukuoka

"Natural farming is a Buddhist way of farming that originates in the philosophy of 'Mu,' or nothingness, and returns to a 'do-nothing' nature. …it is a Buddhist way of farming that is boundless and yielding, and leaves the soil, the grasses, and the insects to themselves.

FUKUOKA FARMING

Fukuoka categorizes modern farming into three main categories of Mahayana, Hinayana, and Scientific: Natural farming is a Buddhist way of farming that originates in the philosophy of 'Mu,' or nothingness...."

"Mahayana Natural Farming: When the human spirit and human life blend with the natural order and man's sole calling is to serve nature, he lives freely as an integral part of the natural world, subsisting on its bounty without having to resort to purposeful human effort. This type of farming, which I shall call Mahayana natural farming, is realized when man becomes one with nature, for it is a way of farming that transcends time and space and reaches the zenith of understanding and enlightenment. Those who live such a life are hermits and wise men." (Masanobu Fukuoka)

"Hinayana Natural Farming: This type of farming arises when man earnestly seeks entry to the realm of Mahayana farming. Desirous of the true blessings and bounty of nature, he prepares himself to receive it. This is the road leading directly to complete enlightenment, but is short of that perfect state." (Masanobu Fukuoka)

"Scientific Farming: Man exists in a state of contradiction in which he is basically estranged from nature, living in a totally artificial world, yet longs for a return to nature. A product of this condition, scientific farming forever wanders blindly back and forth, now calling on the blessings of nature, now rejecting it in favour of human knowledge and action. . .

Cases where scientific farming excels: Scientific methods will always have the upper hand when growing produce in an unnatural environment and under unnatural conditions that deny nature its full powers, such as accelerated crop growth and cultivation in cramped plots, clay pots, hothouses, and hotbeds. And through adroit management, yields can be increased and fruit and vegetables grown out of season to satisfy consumer cravings by pumping in lots of high technology in the form of chemical fertilizers and powerful disease and pest control agents, bringing in unheard-of profits. ..Yet even under such ideal conditions, scientific farming does not produce more at lower cost or generate higher profits per unit area of land or per fruit tree than natural farming." (Masanobu Fukuoka)

Quotes from Fukuoka's book "The Natural Way of Farming"

Four Principles of Fukuoka Farming

"I will admit that I have had my share of failures during the forty years that I have been at it. But because I was headed basically in the right direction, I now have yields that are at least equal to or better than those of crops grown scientifically in every respect. And most importantly:

- My method succeeds at only a tiny fraction of the labor and costs of scientific farming, and my goal is to bring this down to zero.

- At no point in the process of cultivation or in my crops is there any element that generates pollution, in addition to which my soil remains eternally fertile.

- "And I guarantee that anyone can farm this way. This method of do-nothing' farming is based on four major principles: No cultivation. No fertilizer No weeding No pesticides"

- "… as the farmer turns the soil with his hoe, this breaks the soil up into smaller and smaller particles which acquire an increasingly regular physical arrangement with smaller interstitial spaces. The result is harder, denser soil. The only way to soften up this soil is to apply compost and work it into the ground by plowing. But this is only a short-lived measure. In fields that have been weeded clean and carefully plowed and re-plowed, the natural aggregation of the soil into larger particles is disturbed, and the soil particles become finer and finer, hardening the ground."

"When roots reach down into the earth, air and water penetrate into the soil together with the roots. As these wither and die, many types of microorganisms proliferate. These die off and are replaced by others, increasing the amount of humus and softening the soil. Earthworms eventually appear where there is humus, and as the number of earthworms increases, moles begin burrowing through the soil."

"The Soil Works Itself: The soil lives of its own accord and plows itself. It needs no help from man. Farmers often talk of 'taming the soil' and of a field becoming 'mature,' but why is it that trees in the mountain forests grow to such magnificent heights without the benefit of hoe or fertilizer, while the farmer's fields can grow only puny crops?" "We can either choose to see the soil as imperfect and take the hoe in hand, or trust the soil and leave the business of working it to nature."

"The basic strategy for achieving long-term, totally fertilizer-free cultivation on a natural farm is to create deep, fertile soil. There are several ways of doing this. Here are some examples.

- Direct burial of coarse organic matter deep in the ground.

- Gradual soil improvement by planting grasses and trees that send roots deep into the soil.

- Enrichment of the farm by carrying nutrients built up in the humus of the upland woods or forest downhill with rainwater or by other means.

"One may establish an orchard and plant nursery stock using essentially the same methods as when planting forest trees. Vegetation on the hillside is cut in lateral strips, and the large trunks, branches, and leaves of the felled trees are arranged or buried in trenches running along hill contours, covered with earth, and allowed to decompose naturally. None of the vegetation cut down in the orchard should be carried away."

"As I mentioned earlier, the most basic method for improving soil is to bury coarse organic matter in deep trenches. Another good method is to pile soil up to create high ridges. This can be done using the soil brought up while digging contour trenches with a shovel. The dirt should be piled around coarse organic material. Better aeration allows soil in a pile of this sort to mature more quickly than soil in a trench. Such methods soon activate the latent fertility of even depleted, granular soil, rapidly preparing it for fertilizer-free cultivation."

No Fertilizer

"Crops Depend on the Soil: When we look directly at how and why crops grow on the earth, we realize that they do so independently of human knowledge and action. This means that they have no need basically for such things as [manufactured] fertilizers and nutrients. Crops depend on the soil for growth. "I have experimented with fruit trees and with rice and winter grain to determine whether these can be cultivated without fertilizers.

"Of course crops can be grown without fertilizer. Nor does this yield the poor harvests people generally believe. In fact, I have been able to show that by taking full advantage of the inherent powers of nature, one can obtain yields equal to those that can be had with heavy fertilization."

- "Fertilizers speed up the growth of crops, but this is only a temporary and local effect that does not offset the inevitable weakening of the crops. This is similar to the rapid acceleration of plant growth by [added] hormones.

- "Plants weakened by fertilizers have a lowered resistance to diseases and insect predators, and are less able to overcome other obstacles to growth and development.

- "Fertilizer applied to soil usually is not as effective as in laboratory experiments. [Fukuoka cited two examples, but many more have come to light since his book was published].

- "Damage caused directly by fertilizers is also enormous. More than seventy percent of the 'big three' - ammonium sulfate, superphosphate, and potassium sulfate - is concentrated sulfuric acid which acidifies and causes great harm to the soil, both directly and indirectly.

- "One major problem with fertilizer use is the deficiency of trace components".

"The trees of the mountain forests grow under conditions close to pure nature., receiving no fertilizer by the hand of man. Yet they grow very well year after year. Reforested cedars in a favorable area generally grow about forty tons per quarter acre over a period of twenty years. These trees thus produce about two tons of growth each year without fertilizer. This includes only that part of the tree that can be used as lumber, so if we also take into account small branches, leaves, and roots, then annual production is probably close to double, or about four tons. "If we were talking of a fruit orchard here, then this would translate into two to four tons of fruit produced each year without fertilizers - about equal to standard production levels by fruit growers today."

"I am convinced that cultivation without fertilizers under natural circumstances is not only philosophically feasible, but is more beneficial than scientific, fertilizer-based agriculture, and is preferable for the farmer. Yet, although cultivation without the use of chemical fertilizers is possible, crops cannot immediately be grown successfully without fertilizers on fields that are normally plowed and weeded." [Editor's emphasis]

"Following the rice harvest, spread 650-900 pounds of chicken manure per quarter-acre either before or after returning the rice straw to the fields. An additional 200 pounds may be added in late February as a topdressing during the barley heading stage.

"After the barley harvest, manure again for the rice. When high yields have been collected, spread 450-900 pounds of dried chicken manure before or after returning the barley straw to the field. Fresh manure should not be used here as this can harm the rice seedlings. A later application is generally not needed, but a small amount (250-450 pounds) of chicken manure may be added early during the heading stage, preferably before the 24th day of heading. This may of course be decomposed human or animal wastes, or even wood ashes."

"However, from the standpoint of natural farming, it would be preferable and much easier to release ten ducklings per quarter-acre on to the field when the rice seedlings have become established. Not only do the ducks weed and pick off insects, they turn the soil."

"All the trouble taken during preparation of the compost to speed up the rate of fertilizer response, such as frequent turning of the pile, methods for stimulating the growth of aerobic bacteria, the addition of water and nitrogenous fertilizers, lime, superphosphate, rice bran, manure, and so forth -- all this trouble is taken just for a slight acceleration in response. Since the net effect of these efforts is to speed up decomposition by at most ten to twenty percent, this can hardly be called necessary.

Especially since there already was a method of applying straw to the fields that achieved outstanding results."

"I firmly believe that, while compost itself is not without value, the composting of organic materials is fundamentally useless."

No Weeding

"Is There Such a Thing as a Weed?: Man distinguishes between crops and weeds, and the first step he takes in that respect is to decide whether to weed or not to weed. Like many different microorganisms that struggle and cooperate in the soil, myriad grasses and trees live together on the soil surface. Is it right then to destroy this natural state, to pick out certain plants living in harmony among many plants, to call these 'crops' and uproot all the others as 'weeds'?"

"Grasses Enrich the Soil: Rather than pulling weeds, people should give some thought to the significance of these plants. Having done so, they will agree that the farmer should let the weeds live and make use of their strength. Although I call this the 'no-weeding' principle, it could also be known as the principle of 'weed utility'."

"A Cover of Grass is Beneficial: This method includes sod and green manure cultivation. In my citrus orchard, I attempted first cultivation under a cover of grass, then switched to green manure cultivation, and now I use a ground cover of clover and vegetables with no weeding, tillage or fertilizer. When weeds are a problem, then it is wiser to remove weeds with weeds than to pull weeds by hand."

"The many different grasses and herbs in a natural meadow appear to grow and die in total confusion, but upon closer examination, there are laws and there is order here. Grasses meant to sprout do so, those that flourish do so for a reason, and if plants weaken and die, there is a cause. Plants of the same species do not all grow in the same place and way, but some types flourish, then fade in an ongoing succession. The cycles of coexistence, competition, and mutual benefit repeat themselves. Certain weeds grow as individuals, others grow in bunches, and yet others form colonies. Some grow sparsely, some densely, and some in clumps. Each has a different ecology: some grow over their neighbors and overpower them, some wrap around others in symbiosis, some weaken other plants, and some die -- while others thrive -- as undergrowth.

"By studying and making use of the properties of weeds, one weed can be used to drive out a large number of other weeds. If the farmer were to grow grasses or green manure crops that take the place of undesirable weeds and are beneficial to him and his crops, then he would no longer have to weed, in addition to which the green manure would enrich the soil and prevent its erosion."

"I practice a form of rice-barley succession cropping in which I seed barley together with clover over the standing heads of rice, and scatter rice seed and green manure while the barley is up. This more nearly approaches nature and eliminates weeding."

No Pesticides

"Insect Pests Do Not Exist: The moment the problem of crop disease or insect damage arises, talk turns immediately to methods of control. But we should begin by examining whether crop disease or insect damage exist in the first place. A thousand plant diseases exist in nature, but in truth there are none. It is the agricultural specialist who gets carried away with discussions on disease and pest damage. Although research is done on the ways to reduce the number of country villages without doctors, no studies are ever run to determine how these villages have gotten along without doctors. In the same way, when people spot signs of a plant disease or an insect pest, they immediately go about trying to get rid of it. The smart thing to do would be to stop treating insects as pests and find a way that eliminates the need for control measures altogether."

"Most people seem to believe that the use of natural enemies and pesticides of low toxicity will clear up the problem, but they are mistaken. Many feel reassured by the thought that the use of beneficial insect predators to control pests is a biological method of control without harmful repercussions, but to someone who understands the chain of being that links together the world of living organisms, there is no way of telling which organisms are natural enemies and which are pests. By meddling with controls, all man accomplishes is destruction of the natural order. Although he may appear to be protecting the natural enemies and killing the pests, there is no knowing whether the pests will become beneficial and the predators pests. Many insects that are harmless in a direct sense are harmful indirectly. And when things get even more complex, as when one beneficial insect feeds on a pest that kills another beneficial insect which feeds on another pest, it is futile to try and draw sharp distinctions between these and apply pesticides selectively."

===================================================================

Fukuoka Fruit Tree FarmingQuotes from Fukuoka's book "The Natural Way of Farming"

"How much wiser and easier it is to limit oneself to minimal corrective pruning aimed only at bringing the tree closer to its natural form rather than practicing a method of fruit growing that requires extensive pruning each and every year." (pg. 212)

"Orchardists have never tried growing fruit trees in their natural form. To begin with, most have never even given any thought as to what the natural form is. Of course pomologists will deny this, saying that they are working with the natural form of fruit trees and looking for ways to improve on this. But it is clear that they have not really looked in earnest at the natural form. Not a single book or report has been published which discusses pruning based on such basic factors as the phyllotaxy of a citrus tree, or which explains that a divergence of so much gives such-and -such a natural form with primary and secondary scaffold branches of X degrees.

"Many have a vague idea of the natural form as something akin to the shape of a neglected tree. But there is a world of difference between the two.." (pg. 209)

"The natural forms shown from time to time in journals on fruit growing are not all what they are made out to be. These are just abandoned trees of confused shape that have been left to grow untended after having been initially pruned and otherwise cared for." (pg. 212)

"Scientists say that the natural form of a citrus tree is hemispherical with several primary scaffold branches extending out like the ribs of a fan at an angle of from 40 to 70 degrees, but in truth no one knows whether the true form of a citrus tree is that of a large upright tree or a low bush.

"Fruit growers have more or less decided that, if one considers such operations as harvesting the fruit, pesticide spraying, and fumigation, the ideal form of citrus trees grown in a hillside orchard is a round, flat-topped shape measuring at most about 9 feet high and 14 feet in diameter." (pg. 210) "I planted citrus seed and observed the trees growing from these. At the same time, I allowed a large number of various types of citrus trees to go unpruned. From these results, I was able to divine with considerable certainty the natural form of a citrus tree.

"When I reported my findings at a meeting of the Ehime Prefecture Fruit Growers Association, stating that the natural form of the citrus tree is not what it had been thought to be, but a central leader type form, this created a stir among several scientists present, but was laughed off as just so much nonsense by farmers." (pg. 214)

"I adopt the natural form of a tree as the model for the basic tree shape in citrus cultivation. Even when something causes a tree to take on a shape that deviates from the natural form or adapts to the local environment, any pruning and training done should attempt to return the tree to its natural form. There are several reasons for this:

- The natural form permits tree growth and development best suited to the cultivation conditions and environment. No branch or leaf is wasted. This form enables maximum growth and maximum exposure to sunlight, resulting in maximum yields. On the other hand, an unnatural form created artificially upsets the innate efficiency of the tree. This reduces the tree's natural powers and commits the grower to unending labors.

- The natural form consists of an erect central trunk, causing little entanglement with neighboring trees or crowding of branches and foliage. The amount of pruning required gradually decreases and little disease or pest damage arises, necessitating only a minimum of care. However, in natural open-center systems formed by thinning the scaffold branches growing at the center of the tree, the remaining scaffold branches open up at the top of the tree and soon entangle with adjacent trees. In addition, secondary scaffold branches and laterals growing from several primary scaffold branches oriented at unnatural angles (such as in three-stem systems) also crisscross and entangle. This increases the amount of pruning that has to be done after the tree has matured.

- In conical central leader type systems, oblique sunlight penetrates into the interior of the tree, but in open-center systems, the crown of the tree extends outward in the shape of an inverse triangle that reduces the penetration of sunlight to the base and interior of the tree, inviting the withering of branches and attack by disease and pests. Thus, expanding the shape of the tree results in lower rather than higher yields.

- The natural form provides the best distribution and supply of nutrients to the scaffold branches and laterals. In addition, the external shape is balanced and a good harmony exists between the tree growth and fruit production, giving a full fruit harvest each year.

- The root system of a tree having a natural form closely resembles the shape of the aboveground portion of the tree. A deep root system makes for a healthy tree resistant to external conditions." (pgs. 216 & 218)

- The natural forms of young grapevines and persimmon, pear, and apple trees have low branch, leaf and fruit densities, and thus produce small yields. This can be resolved by discreet pruning to increase the density of fruit and branch formation.

- Fruit trees with a central leader system grow to a good height and may be expected to pose climbing problems when it comes time to pick the fruit. While this is true when the tree is still young, as it matures, scaffold branches grow out from the leader at an angle of about 20 degrees to the horizontal in a regular, spiraling arrangement that make it easier to climb. In tall trees such as persimmon, pear, apple and loquat, this forms a framework that can be climbed much like a spiral stairway.

- Creating a pure natural form is not easy, and the tree may deviate from this if adequate attention is not given to protective management at the seedling stage. This can be corrected in part by giving the tree a modified central leader form. To achieve an ideal natural form, the tree must be grown directly from seed or a rootstock tree grown in a planting bed and field-grafted.

- Enabling the seedling to put out a vigorous, upright leader is the key to successfully achieving a natural form. The grower must observe where and at what angle primary and secondary scaffold branches emerge, and remove any unnatural branches. Normally, after five or six years, when the saplings have reached six to ten feet in height, there should be perhaps five or six secondary scaffold branches extending out in a spiral pattern at intervals of about six to twelve inches such that the sixth secondary scaffold branch overlaps vertically with the first. Primary scaffold branches should emerge from the central trunk at an angle of 40 degrees with the horizontal and extend outwards at an angle of about 20 degrees. Once the basic shape of the tree is set, the need for training and pruning diminishes.

- The tree may depart from a natural form and take on an open-center form if the central leader becomes inclined, the tip of the leader is weak, or the tree sustains an injury. There should be no problem though, as long as the grower keeps a mental image of a pure natural form and prunes and trains the tree to approach as closely as possible to that form. A tree that has become fully shaped while young will not need heavy pruning when mature. However, if left to grow untended when young, the tree may require considerable thinning and pruning each year and may even need major surgical reconstruction when fully grown. Considering the many years of toil and losses that may otherwise ensue, it is certainly preferable to choose to do some formative pruning early on." (pgs. 218 & 219)

"… but it might be interesting in some cases to plant seed directly and grow the young saplings into majestic trees having a natural form. Such a tree bears fruit of vastly differing sizes and shape that are unfit for the market. Yet, on the other hand, there always exists the possibility that an unusual fruit will arise from the seed. Indeed, why not multiply the joys of life by creating a natural orchard full of variety and surprises?" (pg. 194) - Masanobu Fukuoka

====================================================================

Orchard Management

Quotes from Fukuoka's book "The Natural Way of Farming"

"Orchard Management: To establish a natural orchard, one should dig large holes here and there among the stumps of felled trees and plant unpruned saplings and fruit seed over the site, leaving these unattended just as one would leave alone a reforested stand of trees. Of course, suckers grow from the cut tree stumps and weeds and low brush flourishes.

Orchard management at this stage consists primarily of coming in twice a year to cut the weeds and underbrush with a large sickle." (pg. 194) "Fruit saplings should be planted at equal intervals along hill contours. Dig a fairly deep hole, fill it with coarse organic matter, and plant the sapling over this." (pg. 193) "Obviously, from the standpoint of natural farming we would expect trees grown from seed to be preferable to grafted nursery stock. … However, when a tree is grafted, the flow of sap is blocked at the graft juncture, resulting either in a dwarf tree that must be heavily fertilized, or in a tree with a short lifetime and poor resistance to temperature extremes.

"While in principle a young tree grown from seed grows faster than grafted stock, I learned that when the initial grafted stock is one to two years old, natural seedlings do not grow as rapidly during the first two or three years and care is also difficult. However, when raised with great care, trees grown from seed develop the most quickly. Citrus rootstock takes more time and sends down shallower roots.

"Citrus trees may generally be grown from nursery plants grafted with rootstock, which, although shallow rooted, are cold-hardy. Apple trees can be trained into dwarf trees by using dwarfing stock,…" (pg. 194) "Weeds: Although the growth of fruit trees among this other vegetation […eulalia and other weeds growing thickly among the brush and assorted trees] was irregular and yielded poor harvests in some cases, there was very little damage from disease and insects.

"Later, with continued cutting back of the underbrush, the non-fruit trees receded and weeds such as bracken, mugwort, and kudzu grew up in their place. I was able to control or suppress weed growth at that point by broadcasting clover seed over the entire orchard." (pg. 195)

"Avoid monoculture of fruit trees. Plant deciduous fruit trees together with evergreen fruit trees and never forget to interplant green manure trees. These may include acacia, myrtle, alder, and podocarpus.

"You may also … interplant some large trees and shrubs, including climbing fruit vines such as grapevine, akebia, and Chinese gooseberry.

"Leguminous green manure plants and other herbs that enrich the orchard soil may be planted as orchard undergrowth. Forage crops and semiwild vegetables can also be grown in abundance, and both poultry and livestock allowed to graze freely in the orchard."(pg. 196)

"A natural orchard in which full, three-dimensional use of space is made in this way is entirely different from conventional orchards that employ high-production techniques. For the individual wishing to live in communion with nature, this is truly a paradise on earth." (pg. 196) - Masanobu Fukuoka

=====================================================================

Diseases, Pests, and PesticidesQuotes from Fukuoka's book "The Natural Way of Farming"

"… I am convinced that by reviving the pest control measures of the not-so-distant past and practicing semi-wild cultivation, people can easily grow more than enough vegetables for their own consumption."

"Because hardy varieties are used, the right crop is grown at the right time in healthy soil, and plants of the same type are not grown together. Companion-planting vegetables of many different types in place of weeds in an orchard or on idle land is an eminently reasonable method of cultivation.

"As an additional precaution, I would also recommend that pyrethrum and derris root be planted at the edge of the garden. Pyrethrum flowers and derris root must be dried and stored as powders. Pyrethrum is effective against aphids and caterpillars, while derris root works well against cabbage sawflies and leaf beetles. However, these may be used against all insect pests, including melon flies, by dissolving the agent in water and sprinkling the solution onto the vegetable plants with a watering can. Both agents are harmless to man and garden vegetables."

"…although from ten to twenty types of pests and diseases generally attack any one kind of vegetable, the only ones that are really major pests are cutworms, borers, leaf beetles, certain types of ladybugs, seed-corm maggots, and aphids."

"Farmers a while back never used pesticides on vegetables in their kitchen gardens. All they did was to catch insects in the morning and evening on some gummy earth at the end of a piece of split bamboo. This worked well for caterpillars feeding on cabbage and other leaf vegetables, melon flies on watermelon and cucumbers, and ladybugs on the eggplant and potatoes. Disease and pest damage to vegetables can usually be prevented by being familiar with the nature and features of such damage rather than attempts at control, and most problems can be taken care of by practicing a method of natural farming that gives some thought as to what a healthy vegetable is."

"Try raising vegetables as the undergrowth in an orchard and let native fowl loose in the orchard. The birds will feed on the insects and their droppings will nourish the fruit trees. This is one perfect example of natural farming at work."- Masanobu Fukuoka

=========================================================================

Greening The DesertApplying natural farming techniques in Africa

an interview with Masanobu Fukuoka, by Robert and Diane Gilman

One of the articles in Sustainable Habitat (IC#14)Autumn 1986, Page 37Copyright (c)1986, 1997 by Context Institute To order this issue ...

Masanobu Fukuoka is another of the major pioneers of sustainable agriculture who came to the 2nd International Permaculture Conference. We spoke with him a few days before the conference while he was visiting the Abundant Life Seed Foundation in Port Townsend, Washington.

He likes to say of himself that he has no knowledge, but his books, including One-Straw Revolution and The Natural Way of Farming illustrate that he at least has wisdom. His farming method involves no tillage, no fertilizer, no pesticides, no weeding, no pruning, and remarkably little labor! He accomplishes all this (and high yields) by careful timing of his seeding and careful combinations of plants (polyculture). In short, he has brought the practical art of working with nature to a high level of refinement.

In this interview, he describes how his natural farming methods might be applied to the world's deserts, based on his experience in Africa during 1985. Translation assistance for the interview was provided by Katsuyuki Shibata and Hizuru Aoyama.

Robert: What have you learned in your 50 years of work about what people could do with their agriculture?

Masanobu: I am a small man, as you can see, but I came to the States with a very big intention. This small man becomes smaller and smaller, and won't last very long, so I'd like to share my idea from 50 years ago. My dream is just like a balloon. It could get smaller and smaller, or it could get bigger and bigger. If it could be said in a brief way, it could be said as the word "nothingness." In a larger way it could wrap the entire earth.

I live on a small mountain doing farming. I don't have any knowledge, I don't do anything. My way of farming is no cultivation, no fertilizer, no chemicals. Ten years ago my book, One Straw Revolution, was published by Rodale Press in the United States. From that point I couldn't just sleep in the mountains. Seven years ago I took an airplane for the first time in my life and went to California, Boston, New York City. I was surprised because I thought the United States was full of green everywhere, but it looked like death land to me.

Then I talked to the head of the desert department at the United Nations about my natural farming. He asked me if my natural farming could change the desert of Iraq. He told me to develop the way of changing the desert to green. At that point I thought that I was a poor farmer and I had no power and no knowledge, so I told him that I couldn't. But from then I started thinking that my task is working on the desert.

Several years ago, I travelled around Europe. It seemed to me that Europe was very nice and beautiful, with lots of nature preserved. But three feet under the surface I felt desert slowly coming in. I kept wondering why. I realized it was the mistake they made in agriculture. The beginning of the mistake is from growing meat for the king and wine for the church. All around, cow, cow, cow, grape, grape, grape. European and American agriculture started with grazing cows and growing grapes for the king and the church. They changed nature by doing this, especially on the hill slopes. Then soil erosion occurs. Only the 20% of the soil in the valleys remains healthy, and 80% of the land is depleted. Because the land is depleted, they need chemical fertilizers and pesticides. United States, Europe, even in Japan, their agriculture started by tilling the land. Cultivation is also related to civilization, and that is the beginning of the mistake. True natural farming uses no cultivation, no plow. Using tractors and tools destroys the true nature. Trees' biggest enemies are the saw and ax. Soil's biggest enemies are cultivation and plowing. If people don't have those tools, it will be a better life for everything.

Since my farm uses no cultivation, no fertilizer, no chemicals, there are many insects and animals living there within the farm. They use pesticide to kill a certain kind of pest, and that destroys the balance of nature. If we allow it to be completely free, a perfect nature will come back.

Robert: How have you applied your method to the deserts?

Masanobu: Chemical agriculture can't change the desert. Even if they have a tractor and a big irrigation system, they are not able to do it. I came to the realization that to make the desert green requires natural farming. The method is very simple. You just need to sow seeds in the desert. Here is a picture of experimentation in Ethiopia. This area was beautiful 90 years ago, and now it looks like the desert in Colorado. I gave seeds for 100 varieties of plants to people in Ethiopia and Somalia. Children planted seeds, and watered them for three days. Because of high temperature and not having water, the root goes down quickly. Now the large Daikon radishes are growing there. People think there isn't any water in the desert, but even in Somalia and Ethiopia, they have a big river. It is not that they do not have water; the water just stays underneath the earth. They find the water under 6 to 12 feet.

Diane: Do you just use water to germinate the seeds, and then the plants are on their own?

Masanobu: They still need water, like after ten days and after a month, but you should not water too much, so that the root grows deep. People have home gardens in Somalia these days. The project started with the help of UNESCO with a large amount of money, but there are only a couple of people doing the experiment right now. These young people from Tokyo don't know much about farming. I think it is better to send seeds to people in Somalia and Ethiopia, rather than sending milk and flour, but there isn't any way to send them. People in Ethiopia and Somalia can sow seeds, even children can do that. But the African governments, the United States, Italy, France, they don't send seeds, they only send immediate food and clothing. The African government is discouraging home gardens and small farming. During the last 100 years, garden seed has become scarce.

Diane: Why do these governments do this?

Masanobu: The African governments and the United States government want people to grow coffee, tea, cotton, peanuts, sugar - only five or six varieties to export and make money. Vegetables are just food, they don't bring in any money. They say they will provide corn and grain, so people don't have to grow their own vegetables.

Robert: Do we, in the United States, have the type of seeds that would grow well in these parts of Africa?

Masanobu: As a matter of fact, I saw quite a few plants including vegetables, ornamentals, and grains here in this town (Port Townsend) this morning that would grow in the desert. Something like Daikon radish even grows better over there than in my fields, and also things like amaranth and succulents grow very well.

Robert: So if people in the United States and Japan and Europe wanted to help the people in Africa and reduce the desert, would you suggest that they send seeds?

Masanobu: When I was in Somalia, I thought, if there are ten farmers, one truck, and seeds, then it would be so easy to help the people there. They don't have any greens for half of the year, they don't have any vitamins, and so of course they get sick. They have even forgotten how to eat vegetables. They just eat the leaves and not the edible root portion.

I went to the Olympic National Park yesterday. I was very amazed and I almost cried. There, the soil was alive! The mountain looked like the bed of God. The forest seems alive, something you don't find even in Europe. The redwoods in California and the French meadows are beautiful, but this is the best! People who live around here have water and firewood and trees. This is like a garden of Eden. If people are truly happy, this place is a real Utopia.

The people in the deserts have only a cup and a knife and a pot. Some families don't even have a knife, so they have to throw rocks to cut the wood, and they have to carry that for a mile or more. I was very impressed by seeing this beautiful area, but at the same time my heart aches because of thinking about the people in the desert. The difference is like heaven and hell. I think the world is coming to a very dangerous point. The United States has the power to destroy the world but also to help the world. I wonder if people in this country realize that the United States is helping the people in Somalia but also killing them. Making them grow coffee, sugar and giving them food. The Japanese government is the same way. It gives them clothes, and the Italian government gives them macaroni. The United States is trying to make them bread eaters. The people in Ethiopia cook rice, barley and vegetables. They are happy being small farmers. The United States government is telling them to work, work, like slaves on a big farm, growing coffee. The United States is telling them that they can make money and be happy that way.

A Japanese college professor that went to Somalia and Ethiopia said this is the hell of the world. I said, "No, this is the entrance to heaven." Those people have no money, no food, but they are very happy. The reason they are very happy is that they don't have schools or teachers. They are happy carrying water, happy cutting the wood. It is not a hard thing for them to do; they truly enjoy doing that. Between noon and three it is very hot, but other than that, there is a breeze, and there are not flies or mosquitoes.

One thing the people of the United States can do instead of going to outer space is to sow seeds from the space shuttle into the deserts. There are many seed companies related to multi-national corporations. They could sow seeds from airplanes.

Diane: If seeds were thrown out like that, would the rains be enough to germinate them?

Masanobu: No, that is not enough, so I would sow coated seeds so they wouldn't dry out or get eaten by animals. There are probably different ways to coat the seeds. You can use soil, but you have to make that stick, or you can use calcium.

My farm has everything: fruit trees, vegetables, acacia. Like my fields, you need to mix everything and sow at the same time. I took about 100 varieties of grafted trees there, two of each, and almost all of them, about 80%, are growing there now. The reason I am saying to use an airplane is because, if you are just testing you use only a small area. But we need to make a large area green quickly. It needs to be done at once! You have to mix vegetables and trees; that's the fastest way for success.

Another reason I am saying you have to use airplanes is that you have to grow them fast, because if there is 3% less green area around the world, the whole earth is going to die. Because of lack of oxygen, people won't feel happy. You feel happy in the spring because of the oxygen from the plants. We breathe out carbon dioxide and breathe in oxygen, and the plants do the opposite. Human beings and plants not only have a relationship in eating, but also share air. Therefore, the lack of oxygen in Somalia is not only a problem there, it is also a problem here. Because of the rapid depletion of the land in those parts of Africa, everyone will feel this happening. It is happening very quickly. There is no time to wait. We have to do something now.

People in Ethiopia are happy with wind and light, fire and water. Why do people need more? Our task is to practice farming the way God does. That could be the way to start saving this world.

Last Updated 29 June 2000.URL: http://www.context.org/ICLIB/IC14/Fukuoka.htm~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE ONE-STRAW REVOLUTION

BY MASANOBU FUKUOKA

Look at this grain! I believe that a revolution can begin from this one strand of straw. Then take a look at these fields of rye and barley. This ripening grain will yield about 22 bushels (1,300 pounds) per quarter acre. I believe this matches the top yields in Ehime Prefecture (where I live), and therefore, it could easily equal the top 'harvest in the whole country . . since this is one of the prime agricultural areas in Japan. And yet . . . these fields have not been plowed for 25 years!

To plant, I simply broadcast rye and barley seed on separate fields in the fall . . . while the rice is still standing! A few weeks later, I harvest the rice and spread the straw back over the fields from which it came.

It is the same for the rice seeding. This winter grain (rye and barley) will be cut around the 20th of May. About two weeks before these crops fully mature, I broadcast rice seed over them. After they have been harvested—and the grains threshed—I spread the resulting rye and barley straw over the field.

I suppose that using the same method to plant rice and winter grain is unique to this kind of farming . . . but there is an even easier way! As we walk over to the next field, let me point out that the rice there was sown last fall at the same time as the winter grain. In fact, the whole year's planting was finished in the field by New Year's Day!

You might further notice that white clover and weeds are also growing in these fields. Clover seed was sown among the rice plants in early October (shortly before the rye and barley). I do not worry about sowing the weeds . . . they reseed themselves quite easily!

So the order of planting in this field is as follows: In early October, I broadcast clover among the rice . . . followed by winter grain in the middle of the month. In early November, the rice sown the previous year is harvested. Then I sow next year's rice seed and lay straw across the field. The rye and barley you see in front of you were grown this way.

In caring for a quarter-acre field, one or two people can do all the work of growing rice and winter grain in a matter of days!

This method completely contradicts modern agricultural techniques. It throws "scientific knowledge" and traditional farming know-how out the window. With this kind of farming—which uses no machines, no prepared fertilizer, and no chemicals—it is possible to attain a harvest equal to or greater than that of the average Japanese farm. The proof is ripening before your eyes.

This way of farming has evolved according to the natural conditions of the Japanese islands, but I feel that "natural farming" could also be applied in other areas . . . and to the raising of other indigenous crops.

In regions where water is not so readily available, for example, upland rice or other grains—such as buckwheat, sorghum, or millet—might be grown. Instead of white clover, another variety of clover, alfalfa, vetch, or lupine might prove a more suitable field cover. Natural farming takes a distinctive form in accordance with the unique conditions of the area in which it is applied.

In making the transition to this kind of farming, some weeding, composting, or pruning may be necessary at first . . . but these measures should be gradually reduced each year. Ultimately, it is not the growing technique which is the most important factor, but rather the state of mind of the farmer.

For 30 years I lived only for my farming and had little contact with people outside my own community. During those years I was heading in a straight line toward a "donothing" agricultural method. The usual way to go about developing a method is to ask "flow about trying this?" or "How about trying that?" . . . bringing in a variety of techniques, one upon the other. This is modern agriculture and it only results in making the farmer busier.

My way was opposite. I was aiming at a pleasant, natural way of farming . . . which results in making the work easier instead of harder. "How about not doing this? How about not doing that?"—that was my way of thinking. By taking this approach, I ultimately reached the conclusion that there was no need to plow, no need to apply fertilizer, no need to make compost, no need to use insecticide! When you get right down to it, there are few agricultural practices that are really necessary.

The reason that man's "improved" techniques seem to be necessary is that the natural balance has been so badly upset beforehand by those same techniques that the land has become dependent on them.

Make your way carefully through these fields. Dragonflies and moths fly up in a flurry. Honeybees buzz from blossom to blossom. Part the leaves and you will see Insects, spiders, frogs, lizards, and many other small animals bustling about in the cool shade. Moles and earthworms burrow beneath the surface. This is a balanced ricefield ecosystem. Insect and plant communities maintain a stable relationship here. It is not uncommon for a plant disease to sweep through this region and leave the crops in my fields unaffected.

And now look over at the neighbor's field for a moment. The weeds have all been wiped out by herbicides and cultivation. The soil animals and insects have been exterminated by poison. The earth has been burned clean of organic matter and micro-organisms by chemical fertilizers. In the summer you see farmers at work in the fields . . . wearing gas masks and long rubber gloves. These rice fields—which have been farmed continuously for over 1,500 years—have now been laid waste by the exploitive farming practices of a single generation.

For centuries, farmers have assumed that the plow is essential for growing crops. However, non-cultivation is fundamental to natural farming. The earth cultivates itself naturally by means of the penetration of plant roots and the activity of micro-organisms, small animals, and earthworms. When the soil is cultivated, the natural environment is altered beyond recognition. The repercussions of such acts have caused the farmer nightmares for countless generations.

For example, when a natural area is brought under the plow, very strong weeds—such as crab grass and docks—sometimes come to dominate the vegetation. When these pests take hold, the farmer is faced with a nearly impossible task of weeding each year. Very often, the land is abandoned.

Moreover, weeds play an important part in building soil fertility and in balancing the biological community. As a fundamental principle, they should be controlled, not eliminated. Straw mulch, a ground cover of white clover interplanted with the crops, and temporary flooding provide effective weed control on my farm.

A local farmer who had expected to see my fields completely overgrown by weeds was surprised to find the barley growing so vigorously among the many other plants. Technical experts have also come here . . . seen the weeds, seen the watercress and clover growing all around . . . and have gone away shaking their heads in amazement.

Twenty years ago—when I was encouraging the use of " nanent ground cover in fruit orchards—there was not a blade of grass to be seen in fields or orchards anywhere in the country. But seeing orchards such as mine, people came to understand that fruit trees could grow quite well among the weeds and grasses. Today, orchards covered with grasses are common throughout Japan . . . and those without grass cover have become increasingly rare.

It is the same with fields of grain. Rice, barley, and rye can be successfully grown while the fields are covered with clover and weeds all year long! Here are some key points to remember when you're dealing with weeds:

As soon as cultivation is discontinued, the number of weeds decreases sharply. Also, the varieties of weeds in a given field will change.

If seeds are sown while the preceding crop is still ripening in the field, those seeds will germinate ahead of the weeds. Winter weeds sprout only after the rice has been harvested . . . but by that lime the winter grain already has a head start. Summer weeds sprout right after the harvest of barley and rye . . . but the rice is alreadv growing strongly. Timing the seeding in such a way than there is no interval between succeeding crops gives the grain a great advantage over the weeds.

Directly after the harvest—if the whole field is then covered with straw—the germination of weeds is stopped short. White clover sowed with the grain as a ground cover also helps to keep weeds under control.

The usual way to deal with weeds is to cultivate the soil. But when you cultivate, seeds lying deep in the earth—which would never have germinated otherwise—are stirred up and given a chance to sprout.

Furthermore, the quick-sprouting, fast-growing varieties are given the advantage under these conditions. So you might actually say that the farmer who tries to control weeds by cultivating the soil is—quite literally-sowing the seeds of his own misfortune!

People interfere with nature, and—try as they maythey cannot heal the resulting wounds. Their careless farming practices drain the soil of essential nutrients .. . and the result is the yearly depletion of the land. If

left to itself, the soil maintains its fertility naturally . . in accordance with the normal, orderly cycle of plant and animal life.

From the time that weak plants first developed as a result of such unnatural practices as plowing and fertilizing, disease and insect imbalance have become a great problem in agriculture. Nature—left alone—is in perfect balance. Harmful insects and plant diseases are always present, but do not occur in nature to an extent which requires the use of poisonous chemicals. The sensible approach to disease and insect control is to grow sturdy crops in a healthy environment.

Furthermore, with natural—as opposed to "organic"—farming, there is no need to prepare compost! I will not say to you that you do not need compost . . . only that there is no need to work hard making it. If straw left lying on the surface of the field in the spring or fall is covered with a thin layer of chicken manure or duck droppings, in six months it will completely decompose.

To make compost by the usual method, the farmer works like crazy in the hot sun . . . chopping up the straw, adding water and lime, turning the pile, and hauling it out to the field. He puts himself through all this grief because he thinks it is a "better way". I would rather see people just scattering straw or hulls or woodchips over their fields!

Scattering straw maintains soil structure and enriches the earth so that prepared fertilizer becomes unnecessary. This, of course, is connected with non-cultivation. My fields may be the only ones in Japan which have not been plowed for over twenty years . . . yet the quality of the soil improves with each season! I would estimate that the surface layer—rich in humus—has become enriched to a depth of more than four inches during these years. This is largely the result of returning to the soil everything grown in the field but the grain itself.

For the most part, a permanent green manure cover and the return of all the straw and chaff to the soil will be sufficient to ensure fertility. To provide animal manure to help decompose the straw, I used to let ducks loose in the fields. If they are introduced as ducklings-while the seedlings are still young—the ducks will grow up together with the rice. Ten ducks will supply all the manure necessary for a quarter acre of land and will also help to control weeds.

Using straw, green manure., and a little poultry manure, one can get high yields without adding compost or commercial fertilizer at all. For several decades now, I have been sitting back, observing nature's method of cultivation and fertilization. And while watching, I have been reaping bumper crops of vegetables, citrus, rice, and winter grain—as a gift, so to speak—from the natural fertility of the earth!

In growing vegetables in a "semi-wild" way—making use of a vacant lot, riverbank, or open wasteland—my idea is to just toss out the seeds and let the vegetables grow up with the weeds. I grow my vegetables on the mountainside . . . in the spaces between the citrus trees.

The important thing is to know the right time to plant. For the spring vegetables, the right time is when the winter weeds are dying back . . . and just before the summer weeds have sprouted. For the fall sowing, seeds should be tossed out when the summer grasses are fading away . . . and the winter weeds have not yet appeared.

It is best to wait for a rain that is likely to last for several days. Cut a swath in the weed cover and put out the vegetable seeds. There is no need to cover them with soil: Just lay the weeds you have cut back over the seeds to act as a mulch and to hide them from the birds and chickens until they can germinate. Usually the weeds must be cut back two or three times in order to give the vegetable seedlings a head start . . . but sometimes just once is enough.

Where the weeds and clover are not so thick, you can simply toss out the needs. The chickens will cat some of them, but many will germinate. If you plant in a row or furrow, there is a chance that beetles or other insects will devour many of the seeds . . . for these creatures walk in a straight line. Chickens also spot a patch which has been cleared and come to scratch around. It is my experience that it is best to scatter the seeds here and there.

Vegetables grown in this way are stronger than most people think. If they sprout up before the weeds, they will not be overgrown later on. There are some vegetables—such as spinach and carrots—which do not germinate easily. Soaking the seeds in water for a day or two, then wrapping them in little pellets of damp clay should solve the problem.

To the extent that people separate themselves from nature, they spin out farther and farther from the center. At the same time, a centripetal effect asserts itself and the desire to return to nature arises.

But if people merely become caught up in reacting—moving to the left or to the right, depending on conditions—the result is only more activity.

The non—moving point of origin—which lies outside the realim of relativity—is passed over, unnoticed. I believe that even "returning-to-nature" and anti-pollution activities—no matter how commendable—are not moving toward a genuine solution if they are carried out solely in reaction to the overdevelopment of the present age.

Nature does not change . . . although the way of viewing nature invariably changes from age to age. No matter the age, natural farming exists forever as the wellspring of agriculture:

NATURAL FARMING CAN WORK FOR YOU!

Just about every farm or garden article you're ever likely to read tells you what to do . . . to grow salsify, make lettuce tents, conquer aphids, or whatever. Every one, that is, except the one on these pages: "The Amazing Natural Farm of Masanobu FUKUOKA." This article tells you what NOT to do . . . and that's where the trouble begins!

Americans, Canadians, and most varieties of Europeans just plain have a hard time NOT doing something. We're all tinkerers by tradition, manipulators of time and space who as often as not don't know when to leave well enough alone (even when something doesn't work, we still call it "progress" or "new and improved").

So when someone like Mr. FUKUOKA—who's grown up in the Eastern tradition of passivity (see, even the word bothers us) in the face of the cosmos—comes along and tells us NOT to do something, we have a darned hard time taking his advice . . . even if we think he's right! It just goes against our grain not to do something.

So if you thought—as we did—that Mr. FUKUOKA's farm is an inspiring, visionary model of what, agriculture should and could be—and if you want to live and farm the same way—your automatic response to the article (right along with ours!) was probably to figure step by step how to put Masanobu's great ideas to work in your fields, orchards, and gardens. Right?

Well join the club. The only problem is that this good, old-fashioned American approach to gettin' things done is 180 degrees opposite to what Mr. FUKUOKA advocates! Since none of us (no, not even the so-called experts) know enough about Nature to tell for sure what's "natural" and what's not . . . there's no way we can run out and one-two-three "naturalize" our farms! We'd just end up with even more tinkering . . . which is exactly what Masanobu wants to avoid.

Having said all that, we should also make it clear that Mr. FUKUOKA does offer some solid, down-to-earth tips on gardening that you can try tomorrow, if you like. (For example, see the sections on mulching with straw and chicken manure . . . or on growing vegetables in semi-wild places.) But the main point of Masanobu's work—to let Nature do as much of the farming as possible—cannot he quickly summed up in a handy set of instructions.

For one thing, Mr. FUKUOKA has developed his techniques in response to particular conditions on his farm and to the needs of his crops. What works for him may or may not work for you. It's good to remember, too, that Mr. FUKUOKA did not succeed overnight. He developed his present method over a period of 30 years . . . and, by his own account, made some pretty spectacular mistakes along the way (for example, he has managed to wipe out an entire mandarin orange grove . . . TWICE).

Furthermore, if Masanobu is right, the knowledge of what is natural for your area and your land will not come from scientific analysis or experimentation . . . but from living on it for many years, sensing its pulse, and coming to love it even as you realize you can never really understand it.

Now, some folks may find this kind of talk too mystical for their taste. But from another point of view, it's just plain common sense. For instance, you don't learn to really know someone you love by jotting down their idiosyncrasies . . . for such an action will only take you farther from your goal. Instead, you just spend time with that individual . . . and, slowly . . . an imperfect but steadily growing knowledge of who he or she is and what he or she needs is sure to emerge.

According to Mr. FUKUOKA, it's exactly the same with the land! While most farmers and gardeners try to figure out how to coax that next apple, plum, or dollar from the soil . . . Masanobu quietly waits for Nature to show the way. What NOT to do then proceeds as "naturally" as water from a spring. —SW.

"The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings," - Masanobu Fukuoka

"Natural farming is a Buddhist way of farming that originates in the philosophy of 'Mu,' or nothingness, and returns to a 'do-nothing' nature. …it is a Buddhist way of farming that is boundless and yielding, and leaves the soil, the grasses, and the insects to themselves."

Four Principles of Fukuoka Farming Fukuoka Fruit Tree Farming Orchard Management Vegetable Gardening Diseases, Pests, and Pesticides The 'Plowboy' interview of Masanobu Fukuoka "My natural way of farming is the sensible one"

http://www.context.org/ICLIB/IC14/FUKUOKA.htm

http://www.motherearthnews.com/library/1982_July_August/The_PLOWBOY_Interview__Masanobu_FUKUOKA

Mother Earth News - Issue # 76 - July/August 1982

The PLOWBOY Interview

Masanobu FUKUOKA -40 Years of Natural Farming

Masanobu FUKUOKA, with his grizzled white beard, subdued voice, and traditional Oriental working clothes, may not seem like an apt prototype of a successful innovative farmer. Nor does it, at first glance, appear possible that his rice fields—riotous jungles of tangled weeds, clover, and grain—are among the most productive pieces of land in Japan. But that's all part of the paradox that surrounds this man and his method of natural farming.

On a mountain overlooking Matsuyama Bay on the southern Japanese island of Shikoku,

FUKUOKA-san (son is the traditional Japanese form of respectful address) has—since the end of World War II—raised rice, winter grain, and citrus crops . . . using practices that some people might consider backward (or even foolish!). Yet his acres consistently produce harvests that equal or surpass those of his neighbors who use labor-intensive, chemical-dependent methods.